|

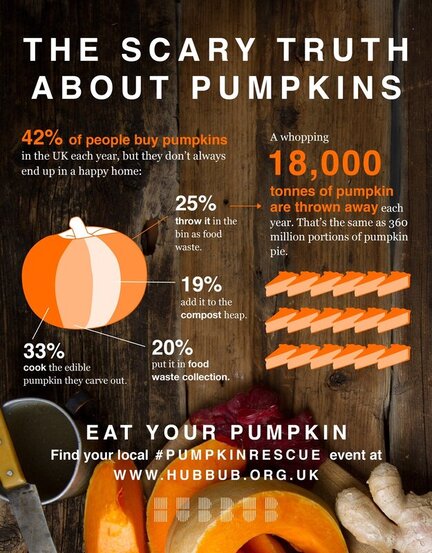

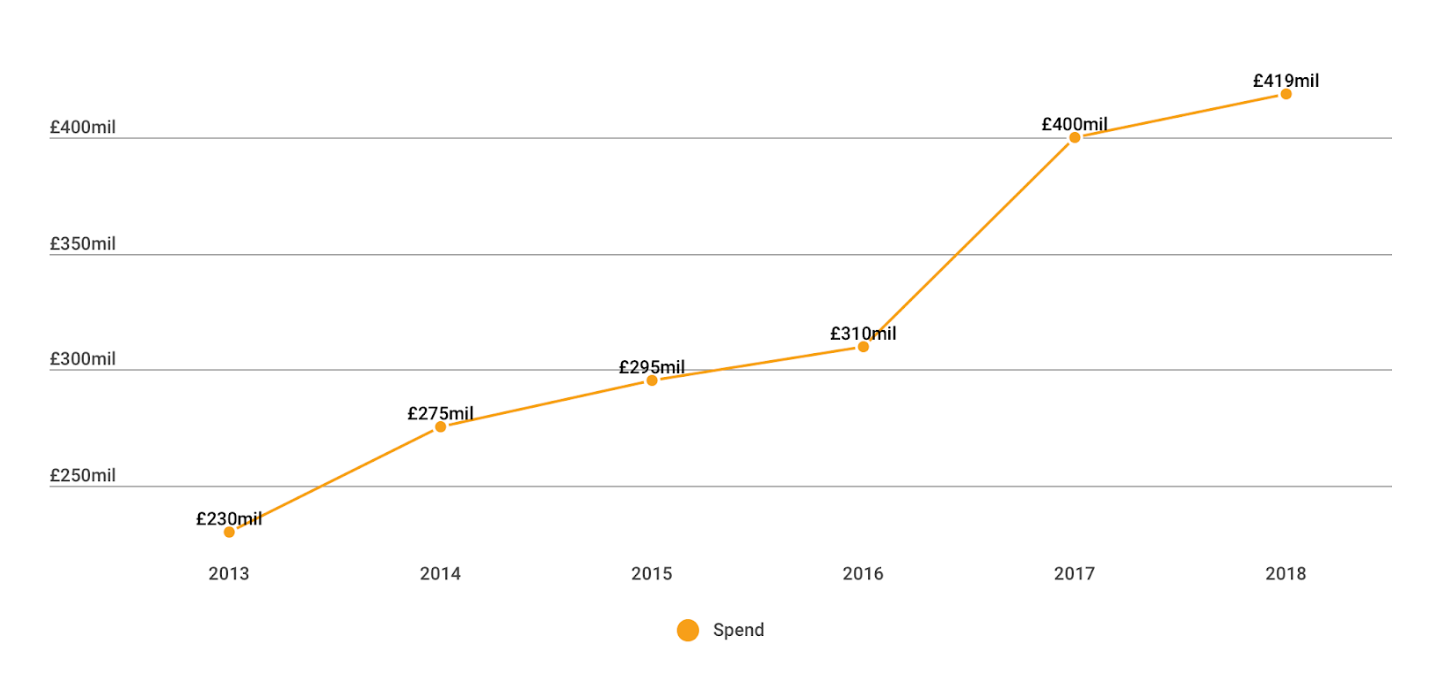

The festivities in the annual calendar when I was growing up (long time ago, sure) were Christmas; and then Easter. There was no Black Friday, no Thanksgiving, and absolutely no Halloween. I don’t mean to be a killjoy - I confess that I have, in the past, gone out with my two kids and a crowd of friends, dressed up to the hilt as ghouls and monsters (the kids, not me) and knocked sheepishly on the front doors of those neighbours game enough to put the right signs up outside their homes, asking for free sweets. Halloween, it turns out, is not a new addition to the festive rota. Actually the origins of Halloween can be traced back to the ancient Celts, across the lands we now know as Britain, Ireland and northern France. This farming community celebrated the end of the bountiful harvest season and the beginning of the cold dark winter with festival of Samhain. The festival symbolised the boundary between the world of the living and the world of the dead. A few invasions and conversions later, Hallowe'en (a contraction of Hallows' Even or Hallows' Evening, or Allhalloween, All Hallows' Eve, or All Saints' Eve), and the last vestiges of Halloween, now a religious festivity, were largely represented by such harmless activities as apple bobbing, whose aim is to see who can retrieve most apples from a barrel of water without using hands. The mid 19th century saw a mass Irish and Scottish migration to North America to escape the devastating consequences of the potato famine, and there, it seems, everything changed. The USA put their relentless commercial spin on Halloween, and it was hastily re-imported into the UK as a new business opportunity, transforming it from a harmless activity into an environmental and health calamity. Today Halloween is a major money-spinner, the UK’s second largest retail festival after Christmas. It was estimated that in 2019 Brits will spend an extraordinary £474 million!  Image courtesy of Finder.com Let’s explore the various bits of Halloween in more detail: Pumpkins Carved out vegetables (mostly turnips) were used in celtic times to represent the spirits of the dead; but in the mid 1800s, irish immigrants found, on US soil, an abundance of something much better: ‘Jack o’ Lantern’ pumpkins, producing a similar effect at a much bigger scale. An estimated 15 million pumpkins are grown in the UK every year – 95% will be carved into hollowed-out lanterns for Halloween. According to food waste organisation Hubbub.org, about 33% of Halloween celebrators say they use the carved out interior of their pumpkin to use for food. However, in the vegetable world, size often compromises flavour and texture, so british pumpkins don’t always translate into a great dinner; but with a blender and a good dose of spices or sugar you can still cook up a soup, stew or pies and cakes. A further 39% claim to put the leftover flesh in the food waste bin or compost heap, while 25% say they put it in the general bin, equating to 18,000 tonnes of wasted food, or 360 million portions of pumpkin pie! Pumpkins that end up in landfill will decompose and eventually emit methane – a greenhouse gas with more than 23 times the warming effect of carbon dioxide. Image courtesy of Hubbub.org Trick or treat In Celtic times on "All Souls' Day", traditionally on November 2, the needy would beg for pastries called soul cakes. In exchange, they would pray for the dead relatives of whoever showed them generosity. This practice was known as "souling," the medieval version of asking for a treat. Today, children no longer ask for nutritious food, but instead compete with each other for sweeter, sugar-dominated sweets and treats. I can’t find the exact amount that Brits spend on sweets (please do let me know if you are able to help me here), but for candy-loving Americans, (and candy selling retailers) Halloween is the high-point of the year. Halloween treats spread way beyond the doorstep treat, and now encompass all kinds of cakes, breakfast cereals and biscuits, that fly off the shelves at the end of October at an otherwise quiet time for retail. According to the (US) National Confectioners Association, Americans are expected to spend $2.5 billion (£1.94bn) on candy this Halloween. According to University of Alabama, American children collect an average of 3,500 to 7,000 calories on Halloween night. It’s hard to say how much of this children actually eat (my kids’ Halloween trophies stayed in their cupboard until I chucked them out in June or July the following year), but the average 13-year-old boy would need to walk more than 100 miles to burn off those candy calories. A few months down the line, I wonder too how many more fillings are being added to children’s mouths! Dressing up in scary Costumes The medieval version of asking if someone wanted a "trick" was known as "guising." On Halloween, medieval children would dress up in costumes and offer a song, poem or joke in exchange for food, wine and money. Today this tradition continues with the sale of millions of cheap items of disposable clothing and accessories, many of which will be used just once before being dumped. It is estimated that 33 million people dressed up for Halloween in 2017 and a shocking four in 10 costumes were worn only once. According to an article in The Metro last week, Halloween costumes sold this year by some of the UK’s biggest retailers will contain the equivalent of 83 million plastic bottles. An investigation of 324 clothing lines sold by 19 retailers found that 83% of the material in the costumes is oil-based plastic. The most common plastic polymer found in the clothing sampled was polyester, making up 69% of the total of all materials. The study predicts that the costumes will add up to 2,000 tonnes of plastic waste in the UK this year. Spraying plastic micro fibres all over your hedges Perhaps the most ridiculous of all Halloween habits is the spraying of fake spider’s webs on your outdoor environments. In my neighbourhood, hundreds of front gardens have white webs all over the hedges bordering their front gardens. It should be noted that these actually look nothing at all like real spider’s webs even in the loneliest and most abandoned spaces. These webs are sprayed from an aerosol can and are plastic-based. Some of this material will inevitably end up on the pavement to be washed down into the drains and then to our waterways in the form of micro-plastics and plastic debris. According to a 2018 report in Nature Geoscience last year, some of Britain’s rivers have more plastic particles in them per square meter than anywhere else in the world. Halloween surely must be contributing to this statistic. I am not against the celebration of this deeply rooted and ancient tradition. But if you are planning to go out for Halloween this evening, take a few minutes to think about how you can do it in a healthier and more sustainable way. Plenty of advice to be found on the internet or on Hubbub’s wonderful website www.hubbub.org. By Clare Brass

5 Comments

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed